Seeds of Transformation: Why Local Action is More Essential Than Ever to Show The Way For International Agreement

The case of a Horizon Europe project advancing transformative action

With the conclusion of recent meetings of main international environmental agreements (COP16 on biodiversity in Cali, Colombia, the COP29 on climate change in Baku Azerbaijan, and the most current failure of the Intergovernmental Negotiating Committee to agree on a legally binding instrument to halt plastic pollution), it becomes increasingly evident that relying on governments and high-level policy to lead the way to transformative change is an uphill battle. While these international platforms involving governments aim to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time—biodiversity loss, climate change, and pollution—in a formidable and complex political environment, some of the resulting agreements are little more than band-aids on a gaping wound.

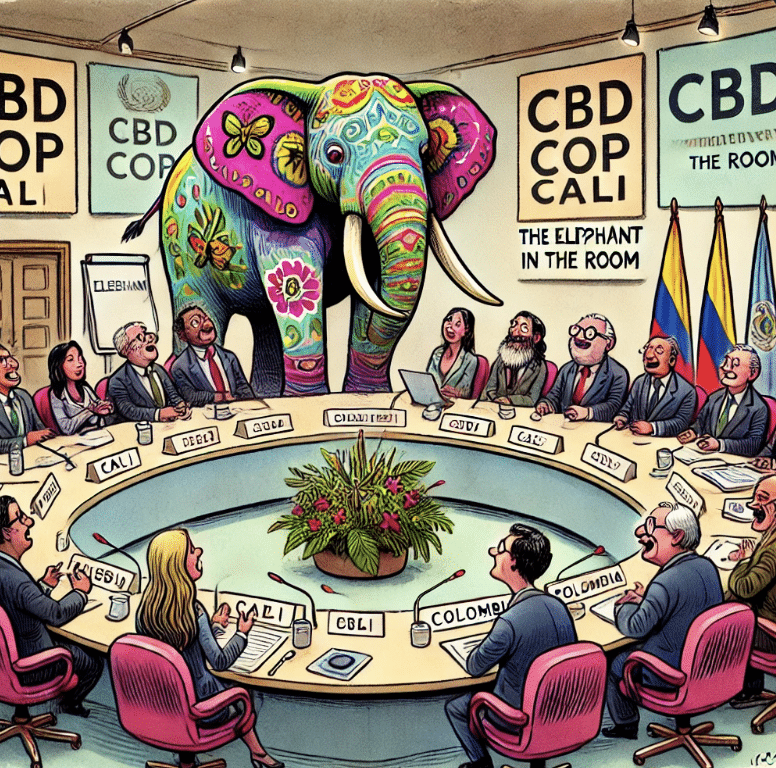

Many might argue we are still better off with them than without them as they bring together the international community, raise awareness, nudge changes and drive voluntary commitments without which we could be in an even more dire situation. Nevertheless, the fact remains that year on year we see the crises of biodiversity loss and climate change worsening, whilst political will and concrete actions to address these crises continue to fall short. Besides, there is the elephant in the room (why we are losing biodiversity and why we have climate change in the first place) that is seemingly difficult to address at these platforms because it would require some major changes in how our societies work.

More commitments and inspiration may be needed from the ground to be channelled into higher level decision-making, steering at least discussions, and subsequent future scenarios on how we vision our future and what changes are necessary. For this, initiatives and projects, such as PLANET4B, that aspire to understand how transformative change (“as a fundamental system-wide reorganization across technological, economic and social factors including paradigms, goals and values”)[1] can be aided and delivering concrete tools at individual and institutional levels are more important than ever.

A Half-Empty, Half-Full Outlook of International Agreements

The COP16 on biodiversity in Cali, Colombia in October, 2024 aimed to follow up on the new global biodiversity strategy to 2030 (the Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework) that sets 23 targets to be achieved by 2030. The meeting in Cali had foreseen that countries that are parties of the CBD (The Convention on Biological Diversity) would provide their national biodiversity plans in line with the global framework prior to the meeting. Yet, 170 countries failed to meet this deadline signalling that biodiversity may not be a priority. Concerning the concrete outcomes, depending on which party is to be asked, the outcomes of COP16 in Cali epitomised “half-empty, half-full”. Biodiversity mainstreaming, one of the main directions to address biodiversity loss, remained relatively vague, calling for good practices and establishment of sectoral communities of practice.

Nevertheless, there were crucial steps forward : the acknowledgement of Indigenous Peoples and local communities as stewards of biodiversity through a Permanent Subsidiary Body, along with the so-called Cali Fund (to share benefits derived from digital sequencing with developing countries voluntarily) as well as decisions on health and biodiversity and marine areas. Meanwhile, however, the conference left critical issues unresolved, particularly around financing mechanisms and implementation frameworks (although negotiations will continue early next year to wrap up these processes).

Elephant in the room ceated by OnenAI

At the COP29 in Azerbaijan, the cycle somewhat repeated with the main discussion being centred around financial mechanisms in particular as a form of support to the Global South to increase abilities and capacities to implement adaptation measures. While the conference resulted in some additional commitments aimed at tackling climate change (e.g. developed nations to provide at least $300 billion annually by 2035 for developing countries to combat climate change, China’s agreement to contribute voluntarily to climate finances, finalising details of the Paris Agreement’s carbon market), it failed to address the phase-out of fossil fuels. Criticism also grew over the sufficiency of financial resources pledged to the Global South resulting in frustration , while concerns were raised over the credibility of the overall COP process due to the perceived influence of fossil fuel interests.

The recent and promising plastics treaty negotiations in Busan at the end of November further underscore the stalled progress and fragility of international commitments. Although countries came together to respond to the major crisis of plastic pollution after a series of negotiations, ultimately, no deal on an international binding instrument was reached. It was reported that oil and polymer producer countries were eager to avoid a production cap on plastics, while other countries advocated for setting global plastic production reduction targets. This divide led to no agreement, albeit with possibilities for future talks on the treaty in 2025.

These recent developments illustrate that whereas there are some small wins, the current outcomes of the treaties offer limited prospects for effectively tackling pollution, climate change, or biodiversity loss. Most importantly, however, in all these intergovernmental dialogues, the elephant in the room looks on in utter bewilderment and asks: how is it that amidst all the lengthy discussions, negotiations, and target setting by our world leaders, the most fundamental question is missing from the conversation: Why is it that, despite knowing the severity of the crises we face, taking action to prevent climate change, biodiversity loss and worsening social inequality are, in practice, never given top priority? Whereas all eyes are looking at financial mechanisms to provide the solution in the form of funds for implementing the agreed actions, their very core aspects are not even questioned (money comes from somewhere, most probably from industry, production, services, which is why we likely have biodiversity loss and climate change in the first place). Debates on values, worldviews and related behaviours and the subsequent lack of prioritisation of main challenges, not only in policy but at all levels of individual and community decision-making, are mostly missing, along with relevant tools and future scenarios of how we can realise different pathways other than the current ones built on fossil-fuel and consumerism. If we do not even address the elephant in the room, how can we expect an even remotely adequate response, while the global crises continue to accelerate impacting the most vulnerable groups first?

Hope Amidst Global Inaction

In these often discouraging times, marked by war, inequality, environmental decline and our perceived inability and unwillingness to address these issues, it can be easy to lose sight of hope. Yet, hope may emerge in the recognition that transformative change can start from the ground up paving the way for global movements. This is where PLANET4B and similar initiatives can come in to bring hope and lead the way.

Photo montage: Coventry University

What inspires hope is not just the grand vision of PLANET4B to trigger biodiversity prioritisation by enacting values and subsequent behaviour, but the tangible, everyday actions it fosters—self-organised activity across communities, including garden journals maintained by partners, community walks that reconnect people with nature, efforts to upscale environmental education as well as studies exploring how we perceive and value biodiversity, and what behavioural, political and social sciences can tell us about steering biodiversity prioritisation more. These actions may seem “tiny” compared to global treaties, but they encompass profound human values—care for people, for nature, and for future generations. Together, they form the seeds of transformation, demonstrating that meaningful change is possible even in the face of systemic failures.

The Unique Role of PLANET4B

Through research and practice, PLANET4B’s mission is to provide knowledge and tools to improve how biodiversity and social equity are prioritised in decision-making, offering a holistic approach to addressing the intertwined challenges of biodiversity loss and social injustice. By moving beyond top-down approaches, PLANET4B focuses on creating transformation through understanding why we act as we do and what influences us to make positive or negative decisions relating to biodiversity and people. Focusing also on community-driven initiatives, PLANET4B further connects place-based, local realities with global goals exploring creative and deliberative methods to advance solutions and transformative pathways that are actionable and inclusive.

Agrobiodiversity Learning Community in Hungary Photo: Katalin Réthy

By amplifying the voices of marginalised groups, such as people with disabilities, migrants or women, PLANET4B facilitates an understanding of shifting towards just solutions, while advocating for systems that value and care for both biodiversity and people. PLANET4B will provide concrete tools (toolkits and guidance for different actor groups to steer transformative change at individual, community and institutional levels, policy recommendations for direct solutions and for overall values change) and scenarios about how our results in sector- and place-based cases can be considered for a more sustainable and just future and upscaled for EU and global processes. Such concrete tools and future scenarios of possibilities can enable the start of a more inclusive conversation about how we are able to steer transformation. Because we will need to start somewhere.

Planting Seeds of Hope and Transformation

In a world where international and national decision-making often lags behind, the work of PLANET4B – and other initiatives that work on the ground – offers a much-needed source of hope. By empowering communities, fostering collaboration, and promoting values-based action, it aims to demonstrate that real change can begin with individuals and local initiatives. These efforts may seem small, but their cumulative impact can be profound. These seeds of transformation are necessary for making desired transformation possible feeding into global processes, even when grander systems fail or take too long – with the hope (and subsequent action) that one day, they will grow even larger, pioneering a path forward.

Learning in nature Photo: Katalin Réthy

The focus on global environmental policies often overlooks the small but impactful actions taken by public and private actors. While global agreements are essential, they must be complemented by systems where efforts at multiple levels can support each other. Encouraging local and smaller-scale initiatives not only steers progress but can also motivate international cooperation. [2] PLANET4B will certainly be ready to do so.

To everyone involved in PLANET4B and other initiatives: Thank You! Your work reminds us that transformative change doesn’t depend solely on global agreements, government or institutions—it emerges from countless small acts of care and determination. So please keep up the good work!

List of references

[1] IPBES (2019). Global assessment report on biodiversity and ecosystem services of the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (pp. 1-1082). Brondízio, E. S., Settele, J., Díaz, S., and Ngo, H. T. (eds). IPBES secretariat, Bonn, Germany. DOI: https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.3831673 [2] Ostrom, E. (2012). Nested externalities and polycentric institutions: must we wait for global solutions to climate change before taking actions at other scales?. Econ Theory 49, 353–369. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00199-010-0558-6